Is zones of regulation neuroaffirming?

Why the Zones of Regulation May Not Be the Best Fit for Autistic Children

The Zones of Regulation is a widely used framework designed to help children identify and manage their emotions through a colour-coded system. While it has gained popularity in schools and therapy settings, there is growing concern that this approach may not be the most effective—or even helpful—tool for autistic children and other neurodivergent individuals.

Does It Promote Compliance Over Authentic Regulation?

The Zones of Regulation approach is often used in a way that emphasises external control rather than genuine self-awareness and emotional regulation. In many settings, children are encouraged to shift out of the ‘red’ or ‘yellow’ zones to reach the ‘green’ zone, which is typically associated with being ‘ready to learn.’ However, this framing risks sending the message that some emotions are ‘bad’ or unacceptable rather than helping children understand and embrace their full emotional experience.

For autistic children, who may experience emotions with greater intensity and may take longer to process them, being told they need to quickly move into a ‘better’ zone can create pressure to suppress or mask their true feelings rather than regulate them in a meaningful way.

Pathologising Natural Emotional States

The Zones of Regulation framework groups emotions into different colours, which can unintentionally label certain emotional states as negative or undesirable. For example, the red zone is often associated with anger and loss of control, while the yellow zone may indicate heightened anxiety or frustration.

The implicit message?

Green is good, red is bad.

But emotions are not inherently good or bad—they are part of the human experience. Autistic individuals, in particular, may experience intense joy, excitement, or distress that doesn’t fit neatly into one category. Teaching children that certain emotions are ‘wrong’ or should be changed can contribute to emotional suppression and difficulty with self-acceptance.

Oversimplification of Emotional Experiences

Emotions are complex, dynamic, and often co-existing. A child might feel nervous and excited at the same time or experience anger mixed with sadness. However, the Zones of Regulation model encourages placing emotions into fixed categories, which may not reflect the full nuance of how autistic individuals experience their feelings.

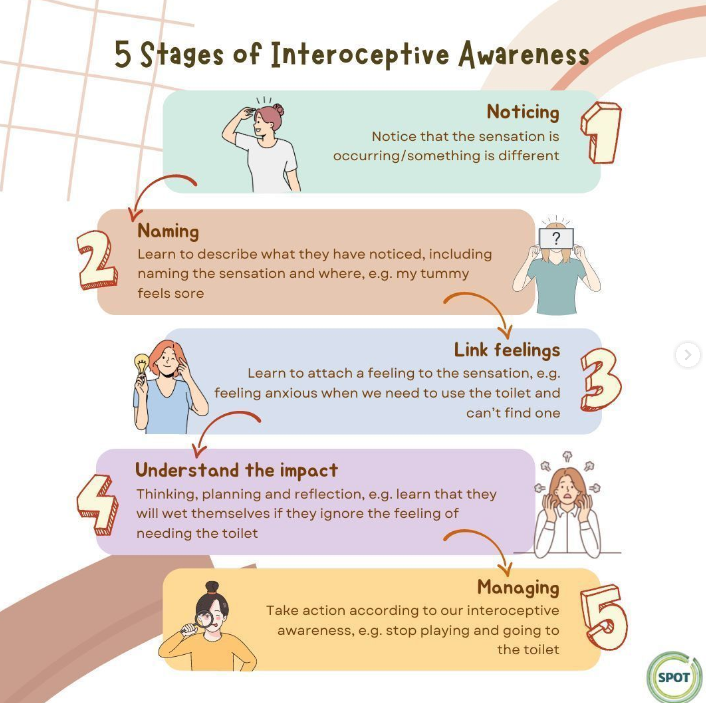

Additionally, many autistic children struggle with interoception—the ability to recognise and interpret bodily signals related to emotions. Simply identifying a colour zone does not support a child in understanding why they feel a certain way or how to meet their needs in that moment.

It Doesn’t Address the Root Causes of Emotional Dysregulation

Many autistic children struggle with emotional regulation not because they need to be trained to shift zones but because they experience sensory overload, unmet needs, or executive functioning challenges. Instead of focusing on why a child may be dysregulated—such as an overwhelming environment, social exhaustion, or an unmet sensory need—the Zones of Regulation model often shifts the focus to changing the

For example:

If a child is in the red zone because they are overwhelmed by loud noise, the solution isn’t to ‘calm down’ into the green zone—it’s to reduce the sensory input or provide tools that support their sensory needs.

May Encourage Masking Rather Than Genuine Self-Regulation

A major risk of using Zones of Regulation with autistic children is that it can reinforce masking—the act of suppressing natural responses to fit into expected social norms. If children are frequently praised for being in the green zone and encouraged to move out of other zones as quickly as possible, they may learn that showing distress, frustration, or excitement is not acceptable.

Long-term, masking emotions can contribute to burnout, anxiety, and difficulty recognising one’s own needs, making self-regulation even harder.

Lacks a Neuroaffirming Perspective

The Zones of Regulation was not designed specifically for neurodivergent individuals, and it does not fully align with neuroaffirming principles. Neuroaffirming approaches prioritise:

Validating all emotions rather than categorising them as ‘good’ or ‘bad.’

Recognising that emotional regulation is not about compliance but about meeting needs and feeling safe.

Encouraging co-regulation—helping children regulate through connection and support rather than expecting them to do it alone.

What Are the Alternatives?

Rather than relying on Zones of Regulation, here are some alternative approaches that better support autistic children:

1. Co-Regulation Over Self-Regulation

Many children—especially autistic children—regulate best through connection with a trusted adult. Instead of expecting a child to manage intense emotional states alone, focus on co-regulation: offering reassurance, presence, and sensory or relational support. This might look like sitting quietly beside a child, offering a grounding touch (if welcome), or simply narrating what you notice gently and without judgment.

Listening to the child’s experience, reflecting back some of the emotions you think they might be feeling, and helping them name those experiences builds both emotional literacy and safety—both of which are prerequisites for true self-regulation.

While “independent self-regulation” is often the goal in school-based settings, for many children—especially those who are neurodivergent or trauma-affected—co-regulation is the bridge that gets them there. Check out this resource from Revolution in Education - providing descriptions of co-regulation practices occurring in the school context.

2. Interoception-Based Approaches

Emerging research highlights interoceptive awareness—the ability to notice and interpret internal body signals—as a foundational building block for emotional regulation and emotional intelligence. This is particularly relevant for autistic children and those with trauma histories, for whom top-down, purely cognitive strategies (like those used in Zones of Regulation) can be difficult to access—especially in moments of heightened stress or dysregulation. As Dan Siegel puts it, when a child has “flipped their lid,” reasoning and categorising become neurologically out of reach. Interoception-based approaches instead focus on bottom-up awareness: helping children notice what’s happening in their body first, then supporting them to respond. The South Australian Department for Education has created accessible, practical resources around this approach, which also aligns with evidence-based models like Mindfulness and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. Kelly Mahler (Occupational Therapist) also has fabulous resources for understanding behaviour, emotions and building interoceptive awareness.

3. A Neuroscience-Informed Approach to Regulation

Contemporary neuroscience makes it clear: emotional regulation is not just a behavioural skill—it’s a biological and relational process. Children need to feel safe, both internally and relationally, in order for their nervous systems to support calm, connected states.

Rather than focusing on behaviour, a neuroscience-informed lens helps us understand why a child might be dysregulated in the first place—and what they need to return to regulation. This might include sensory adjustments, time, or connection.

This idea is central to Dr. Dan Siegel’s work in The Whole-Brain Child, where he introduces the concept of “Name it to tame it.” The process of identifying and naming an emotional experience helps integrate the brain’s emotional and rational parts, but it doesn’t happen in isolation—it requires a calm, attuned adult and a sense of felt safety.

Unlike behaviourist approaches that focus on observable behaviour and reward-based compliance, neuroscience-informed models prioritise emotional safety and relational support as the foundation for lasting regulation.

💡 Learn more about this concept in Dan Siegel’s The Whole-Brain Child or watch him explain “Name it to Tame it” on YouTube.

4. Building Emotional Literacy Through Strengths-Based Validation

Helping children regulate emotions starts with helping them understand them. Instead of asking children to categorise their feelings into predefined zones, we can nurture emotional literacy through strengths-based validation and accessible, everyday tools.

This might include exploring emotions through classroom texts, having a visible list of feeling words to expand vocabulary, or modelling reflective language like, “I notice my tummy feels tight—maybe I’m worried about something?” These small moments help children connect internal sensations (interoception) with emotional meaning, without pressure to “fix” what they’re feeling.

By validating their internal experience—rather than rushing to manage it—we help children develop a more authentic relationship with their emotions. One that’s grounded in curiosity, acceptance, and language they can build on.

In summary

While the Zones of Regulation may work for some children, it has significant limitations when used with autistic and trauma affected individuals. By shifting away from compliance-based emotional regulation and towards neuroaffirming, co-regulation-based approaches, we can create safer, more supportive environments where autistic children feel truly understood and empowered.

Rather than teaching children to change how they feel, let’s teach them that all emotions are valid, their needs matter, and they deserve support in a way that honours their neurodivergent experience.